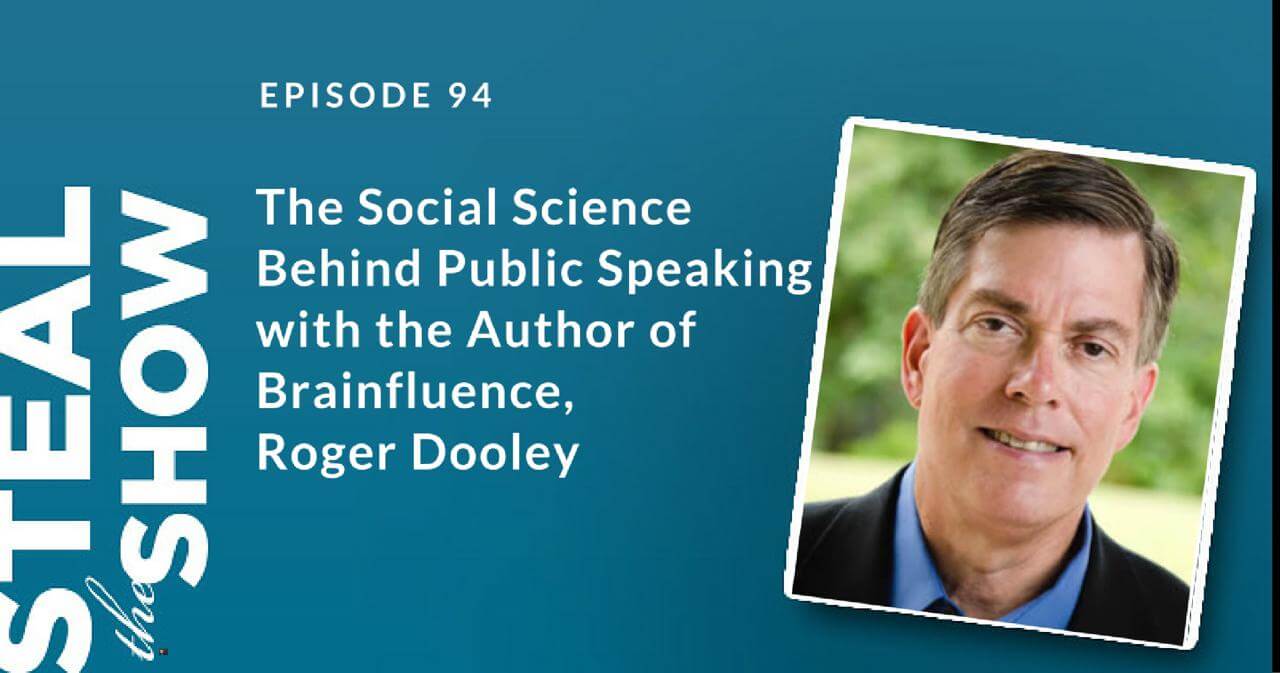

00:00 Michael Port: Welcome to Steal the Show with Michael Port. This is Michael. Today’s guest is Roger Dooley, and he’s the author of “Brainfluence: 100 Ways to Persuade and Convince Consumers with Neuromarketing.” He also writes the popular blog under the same name, Neuromarketing, as well as Brainy Marketing at Forbes.com. He’s the founder of Dooley Direct, a marketing consultancy, and he’s the co-founder of College Confidential, the leading college-bound website. Now that company was purchased. It was acquired by Hobsons, a unit of UK-based DMGT, where Dooley served as the vice president of digital marketing and continues in a consulting role. Currently, Roger is focused on spreading his ideas through writing and speaking, with limited engagements for training, coaching, and facilitation.

00:54 Roger Dooley: Hey, Michael, how are you?

00:56 Michael Port: I’m doing very well. Last time we were supposed to record, was the day that my boat caught on fire, so that had to be cancelled. But I’m glad we’re here now. I’m glad I’m alive, that’s number one, and I’m glad that I’m here now and thank you for changing your schedule around.

01:14 Roger Dooley: Oh, no problem, sorry to hear about your boat.

01:16 Michael Port: Let’s talk about persuasion. You are an absolute expert on persuasion. And you are a research-based expert on persuasion and what is public speaking and performance but persuasion? So, I’d love your definition of persuasion and do influence and persuasion go hand-in-hand? And maybe an example of how this is the case.

01:47 Roger Dooley: Well, not necessarily in the same order that you asked, Michael, but I think influence and persuasion often are used almost synonymously. So, I do think they go hand-in-hand. I think that persuasion implies bringing other people around to your point of view or getting them to do something that you would like them to do. Influence is perhaps a little bit more elemental of establishing your own credibility and believability, and so on. I think that there are certainly a lot of experts out there, but I like to go back to the science when I’m talking about persuasion and influence, because there is a big body of research out there that can really guide us, and is better sometimes than relying on a guru saying, “Hey, this worked for me, so maybe it’ll work for you.”

02:43 Michael Port: Persuasion tends to have a negative valence to it, so how do you respond when people interpret persuasion as manipulation?

02:54 Roger Dooley: That is something that I get all the time when I… Particularly, if I’m doing a speech and I’ve shown folks 25 different ways to be persuasive using science. I inevitably get the question, “Well, is this manipulation?” To the point where I now actually include a few slides about, “Is this manipulation?” And I think that any tool used improperly can be manipulation. It can be unethical, it can be immoral. I like to go back to the famous sales expert, Zig Ziglar, who said, “The most important persuasion tool that you have is your own integrity.” And I think by that, he meant that if you are using your tools of persuasion and your abilities to get somebody else to a better place, that they’ll appreciate you helping them get there, then it’s fine. It’s not unethical, it’s not manipulation, you’re helping them. Now, on the other hand, if you’re using these tools to sell people stuff they don’t need, that they’re not gonna be happy with and so on, then sure, that is manipulation and it’s not ethical and you shouldn’t do it.

04:03 Michael Port: What are some of the craziest myths that you’ve heard about persuasion tactics, if you have heard any at all? But I got to imagine there are myths out there, since you’re a science-based expert in this. What do people think is persuasive that really isn’t? Do you have anything on that?

04:25 Roger Dooley: Well, I think maybe the biggest myth is that there is some kind of a magic bullet that you if you do this one thing, you will be persuasive, or learn this one skill. In fact, most persuasion or influence-building is situation-based. It depends on the individual that you’re talking to. So there’s no one technique or one approach that works. Often you need a variety of techniques in the same way that if you’re an expert on speaking and if somebody said, “Well, the one thing you need to know is body language. If you can get your body language right, then everything else will fall into place.” And I’m sure you’d say, “Well, yeah, that’s important but there’s other stuff too.”

05:10 Michael Port: That is absolutely right. That’s one of the things that I worry about just generally in education, whether it’s lower-level education for kids or professional education, is teachers that have a myopic view of the topic and solutions that are specific only to that view. Because there are so many ways to approach the results that we wanna produce, and I love how you… You’re very broad in your thinking and you’re very nuanced, and I imagine a lot of that comes from being a researcher rather than an opinionator.

06:03 Roger Dooley: Well, I don’t even know if I would call myself a researcher exactly, but I do enjoy studying the work of many, many researchers who are actually doing the hard work. I’m sort of digesting the stuff that they’re putting out, which is often incomprehensible [laughter] academic papers and then turning that into some kind of actionable advice that normal people can understand and use.

06:27 Michael Port: That’s incredibly helpful, and I do thank you for it, because there’s a certain number of authors, yourself included, that do that for us. Because first of all, it’s often very hard to find the research on the subjects that you’re interested in, because it’s published academically, but the researchers have no desire to go out in the world and promote it. And it’s also often hard to understand and put into context, and you do a great job of that. So you mentioned that you give a presentation, say, for example where you have 21 tips on how to be more persuasive. How about let’s start there? I’m not asking for 21 right now, but let’s start with three tips that people can use right away to be more persuasive in their every day life. And then, maybe we’ll also see if we can apply that to the stage. How would these techniques that people can use for persuasion in every day life also apply to what they’re doing when they’re presenting in front of a group of people?

07:32 Roger Dooley: Alright, well, maybe I can start off with six or seven, although we won’t go through them all. But one very basic starting point for anybody who wants to study influence is Robert Cialdini and his first and amazingly best-selling book, three million copies sold, “Influence”, and then his newest book, “Pre-suasion”. And in “Influence”, he introduced six principles of persuasion that he said underlie just about, actually, or influence, that he says underlie many of the very specific techniques that we could talk about, so that you might pick some particular little quirky technique that you found to work and chances are it might relate to one of those six basic principles. And then in his newest book, he actually introduced a seventh, 30 years later.

08:27 Roger Dooley: So for Influence geeks, that’s really big news. But one of his is liking. And basically, that is showing things that you might have in common with the person you’re speaking with, so that they will tend to like you and you will be, in that case, more effective at persuading or influencing them. And so, one thing that I always try and do at the beginning of a speech is to find something that I have in common with the audience. A couple of years ago, I did a series of talks to a bunch of IT service providers and I had a period in my life where I founded and ran a small IT service company, so you better believe that I led immediately with that. Sometimes you have to go to something broader. I could talk about one of my entrepreneurial struggles at the outset that would relate to really a wide variety of businesspeople if we didn’t have that really specific tie. But the more you can show what you have in common, and this isn’t just in front of an audience, you could do it on your website, you could do it in your printed material and so on, the more they will tend to feel good about you and you will find that you are more credible and persuasive.

09:53 Michael Port: That’s wonderful, because that’s one of the steps in the development of a speech is to identify and be able to articulate that you understand the way the world looks to the audience, because if they don’t think you understand the way the world looks to them, even if they like your idea, even if they think it may be helpful to them, it’s easy for them to say no. It’s easier for them to say no if they think that it’ll be confronting or difficult and they have to get over that hurdle in order to adopt that big idea or go after that promise. And if they think you don’t get them, even though you’ve got great ideas, there’s an out. “No, he doesn’t really understand me. It’s a little different for me.” But if they say, “Man, he really understands me. I gotta tell you. This guy just… He just hit me right between the eyes. He knows exactly where I am and you know what? He’s right and I want that thing he’s talking about.” I don’t mean a product. I mean, “I want to experience that way of being in life,” or “I wanna be able to produce that result for myself.” Then they’re much more likely to say yes.

11:04 Roger Dooley: Right. And it’s true. And I think the liking isn’t even necessarily that deep. Something that I do for just about all of my audiences is ask how many pet owners there are in the room. And typically, probably two-thirds of the hands go up and then I do about 20 seconds with a few amusing photos of my dog as a puppy and as a grown dog. And what I use that is an example of building liking, because in those 30 seconds, I’ve established something that may not be at all related to the topic that I’m talking about or the audience, but I’ve established that I’ve got something in common with them. And that really, even though it’s largely irrelevant, it still can establish that liking effect.

11:57 Michael Port: Fantastic. So that was number one, was liking.

12:01 Roger Dooley: Right, well, something else that is commonly used in many, many forms is another one of Cialdini’s principles and is social proof. And that is showing that other people like you, like your stuff, they use your stuff. If you’re selling a product, it might be the number of people who have bought the product, it might be the number of amazing reviews that you have. But it comes in many forms, but that is something that can be quite powerful. And in a speech, you certainly don’t want to get up there and brag about how successful you are, but if you have a way of working in something showing that your ideas have been adopted by many people or something along those lines, that will make you more persuasive as well.

12:56 Michael Port: And does it…

12:57 Roger Dooley: You see it all the time on websites where people will show, “We have 38,000 subscribers to our newsletters or a million customers worldwide,” that kind of thing.

13:05 Michael Port: What has Burger King said? “Over three billion sold,” something like that?

13:09 Roger Dooley: Well, that was McDonald’s, actually. I think they stopped doing that. They got tired of updating their signs.

[laughter]

13:17 Michael Port: Or maybe because they’re not thought of as the healthiest food, people might start thinking, “Oh, my God. We’ve eaten a lot of that stuff.” They might feel it would work against them.

13:27 Roger Dooley: Over 10 million heart attacks caused.

13:29 Michael Port: Yeah.

13:30 Roger Dooley: But they actually… That was a very effective use, particularly when they were growing, when people hadn’t heard of McDonald’s, perhaps. And this was probably before your time, and maybe even a little bit before mine, at least as far as thinking like marketers. When they would open a store in a new area that wasn’t familiar with McDonald’s, showing that they had served eight million, which at that point seemed like a pretty big number, although with their current numbers, it’s pretty small…

13:56 Michael Port: I imagine.

13:57 Roger Dooley: But that was an effective form of social proof for them.

14:00 Michael Port: Oh, that’s great. So we have liking, we have social proof.

14:03 Roger Dooley: Right. Well, let’s see. Oh, another one of his is reciprocity, but that is sometimes a little bit tough to do from the stage. And that is if you give somebody something with no expectation of return, then you will be more likely to persuade that person or influence that person to do something for you. And although it isn’t exactly from the stage, this technique is from really the master himself, Robert Cialdini. I’ve been fortunate enough to meet him a few times and attend some of his talks. And something that he does after every talk is has an assistant or assistants stand near the back of the room at the end and they give people a little laminated card that has his six principles of persuasion, which I guess now he’s gonna have to redo to now make it seven. But he would… These folks who just hand it out to the folks in the back of the room. And in addition to the principles with basically just their name and maybe a one-line explanation of what it was, of course, there would be a little promo for his business there, that they do consulting and speaking, and so on. And what this was is an attempt to establish reciprocity.

15:30 Roger Dooley: He’s giving you this nice little card that summarized the key points of the speech that you just heard with no expectation that you are going to do anything. And of course 99.9% of the people who get that little card don’t actually call him up and hire him as a consultant, but it has predisposed them to appreciate him more, because he has established reciprocity. And one of the key things about reciprocity is that it doesn’t have to be a really big thing. Some very small favor can then establish that feeling that, “Okay, this person did something for me.” And this, of course, is non-conscious on the part of the other person. “This person did something for me, so now I’ll probably do something for them if they would ask.”

16:19 Michael Port: Sure. There are many, many things you can do at the beginning and the end of a presentation that would leverage this particular principle of reciprocity. One of the things that our friend, Mike Michalowicz, does from time to time, at the end of his speech when he is mentioning that there’ll be evaluations to fill out, which is common at events, he says, “Listen, guys. The organizers are gonna go around and give you an evaluation and I gotta tell you, I’m just so, so, so incredibly thrilled, because you guys have been a 10 audience. My experience with you has been remarkable. On a scale of 1 to 10, you’re a 10. And I just wanna thank you for that.” Well, I don’t know if he studied it, but I’m gonna go out on a limb and say, “You know what? That is a little bit of pre-suasion that is demonstrating some reciprocity. Even though he didn’t do something for them, he is telling them that they are really wonderful, and then as soon as they go to evaluate him, they might think, “Well, he said I’m a 10, I can’t give him a six.” [laughter] That wouldn’t be nice. Maybe there’s some reciprocity involved in there. Yeah? What do you think?

17:48 Roger Dooley: Well, yeah, it could be that. And I see a couple of other persuasive techniques that are different, but both embodied in that little ploy, which I like and I might have to steal. First of all, he’s created an anchoring effect. When you give somebody a number, it will then influence the numbers that they think about. And the classic experiment was a Dan Ariely experiment, where he had his subjects write down the last two digits of their Social Security number on a piece of paper. And of course, in essence, that’s a random number there, because everybody has different numbers and the last two in particular mean absolutely nothing. But it gave him a random number between 00 and 99, and then he asked them to estimate the price of different items, particularly things they wouldn’t be too familiar with because, obviously, if it’s an item that you really know about, then you’re gonna provide an accurate answer.

18:46 Roger Dooley: But he asked some things like a computer keyboard, which I don’t know when the last time you bought a computer keyboard was, but it’s not a frequent purchase, and they vary a lot. So, you wouldn’t really have a clue from looking at a picture as to what it was worth. And what he found was, the folks that had been primed in the lowest bracket, which would be the 0 to 19, came up with a rather low estimate. I think it was on the order of $16 or $18 for their computer keyboard. And every 20% bracket, every quintile, you went up, the estimate of the value of that keyboard or the price of the keyboard got higher and higher, until the final group was up in the $50 range. And those are the folks that had been in the 80 to 99 range.

19:36 Roger Dooley: So, this totally irrelevant number dramatically affected people’s perceptions of what the item would cost that they weren’t really too familiar with. So by furnishing these folks with a 10 as an initial prime, Mike was really predisposing them to a higher number since that was the top of the scale.

19:58 Michael Port: That’s fascinating.

19:58 Roger Dooley: So, that’s one thing. And the another principle, Michael, is flattery. Flattery is an influence technique and you will think better of a person who says nice things about you. And they’re really interesting. And that doesn’t sound like too much of a surprise, but you think, “Okay, but yeah, they’re gonna know that I’m trying to sell them something, so they’re not really gonna believe it’s genuine.” Because if you were in that audience and the audience seemed like an average audience to you, and Mike says, “Wow, you’re a 10.” You might say, “Yeah, I think he’s probably laying it on a little bit thick here.” But experiments show that even when you doubt the flattery, even if you think they have an ulterior motive, you are still affected by that flattery. You still think better of them and are more likely to be persuaded.

20:48 Michael Port: Wow!

20:49 Roger Dooley: So, that’s a really powerful tool to use. And not just from the stage, but in every day life.

20:54 Michael Port: That’s fascinating. Going back to anchoring, it’s one of the reasons that I very strongly suggest people do not use self-deprecating humor about poor performance. I’ve seen people go up and say, “Oh, my God, I’m so sorry you have to listen to me today but I’ll… ” No, no, no, no, because you’re anchoring that right at the beginning and that’s not setting a great tone. It’s not uncommon for folks to do that kind of thing because they’re a little bit nervous, and they are trying to lower expectations, in a sense, because they don’t want people to think that they’re gonna be great and then if they’re not, they’ll be disappointed. But when you lower expectations that much, it seems like you’re anchoring this negative association and then people go, “Oh, okay. Well, I guess it’s not gonna be that good.”

21:49 Roger Dooley: Well, yeah. Michael, there’s a good analogy to wine there, of all things. One of the favorite experimental tools of psychologists is Two Buck Chuck. And I don’t know if you’re familiar with it, but…

22:05 Michael Port: Yeah. Yeah. I’ve heard of it. I’ve heard of it.

22:06 Roger Dooley: It’s a Charles Shaw wine from Trader Joe’s…

22:08 Michael Port: Yeah.

22:08 Roger Dooley: And now it costs about three bucks a bottle and two bucks are gone but it still retained the name, Two Buck Chuck. And the reason psychologists like to use it is because it’s cheap, for one, it tastes more or less wine-like. In other words, if I gave you a taste you’d say, “Oh, that’s red wine.” And it’s consistent, because it’s mass-produced, so you don’t have to really worry that one bottle is gonna be greatly different from another bottle. And what they found is that people’s expectations about the wine really affect their perception of it. They put people in an FMRI machine and gave them a taste of wine and asked them what they thought about it. But they also measured their brain activity at the same time so they could see what their brain was experiencing. And they gave them a taste of Two Buck Chuck and in some cases, they thought it was a $5 wine, which is pretty accurate, that’s more or less what it was. And in the other cases, they thought it was a $45 wine.

23:15 Michael Port: Wow!

23:15 Roger Dooley: So a rather nice, expensive wine. And as you might expect, people who thought they were drinking the $45 wine said it tasted better, which yeah, I mean you would do the same thing. If you were at a friend’s house and they said “Hey, I just got this wine. It’s 50 bucks a bottle, what you think?” You’re not gonna say, “Meh, I’ve had better for 10 bucks.” You’d say, “Ah, it’s good, it tastes nice, it’s interesting, complex.”

23:37 Michael Port: Sure, sure.

23:38 Roger Dooley: But what they found that was really startling was that the areas in the brain associated with pleasure lit up more for the $45 wine, it was of course, Two Buck Chuck. So not only did these folks say they liked the wine better, they actually experienced a better wine. So, setting expectations at the outset, and this is something that applies to any kind of product. If you can set expectations that are high and then reasonably meet those expectations, you will actually be perceived of as being better. I think the key thing is it has to be plausible. Now typically, the people tasting this wine were not sommeliers, they experienced wine that tasted pleasant and they were willing to believe that it was an expensive wine. If they tasted it and it would taste like vinegar, then all the expectations in the world wouldn’t help.

24:37 Michael Port: So if you were surveying a group of experts, the results of the experiment are gonna change dramatically. It seems like in the experiments that you’re mentioning, most of the people did not have expertise on that particular, in either topic with wine or subject matter with, say, the keyboard.

25:05 Roger Dooley: Right.

25:06 Michael Port: But if you had a…

25:07 Roger Dooley: The more you’re an expert, the less likely you are to be influenced by more or less irrelevant factors, because the price, it should be irrelevant to the taste of the wine. You should be tasting it for how it tastes, but it is another piece of information. And that’s really the way we perceive the world. We are constantly looking for cues about something that will help us understand what we’re seeing or hearing or tasting or whatever. It’s not just the sort of obvious information that we’re given.

25:40 Michael Port: It’s so interesting. Often, they say that there are certain athletes that are often paid more than others even though their performance isn’t better than others, because they look the part more than the other athletes. So even in young athletes when you see, say you have these kids on a baseball team and one of them just looks like a baseball player, the way he moves, he’s got the body for it. But there’s another guy on the team who just doesn’t look like a baseball player, he’s a little bit lanky, and maybe he doesn’t look super coordinated, but he has a better batting average and a higher fielding average.

26:28 Roger Dooley: Right, that’s the Moneyball principle there, where the key insight that enabled, was it the Oakland team to be a much better recruiter and compete more effectively than their budget would suggest was that they looked at the stats, the important stats, and ignored all those other factors.

26:50 Michael Port: That’s very interesting. So we have liking, social proof, reciprocity, anchoring, flattery and…

26:55 Roger Dooley: Okay, well the new principle, can’t let this go without telling you what Cialdini’s newest principle, number seven…

27:06 Michael Port: I just started reading the book.

27:07 Roger Dooley: Oh, this is a spoiler, then. Do you want me to go ahead or should I stop?

27:09 Michael Port: No, no, go ahead, go ahead, please. [chuckle] That would be horrible for my audience if I said, “No, no, no, don’t tell me.” It’s like the…

27:18 Roger Dooley: Yeah, they’d all have to go out and buy the book. So now, it is unity, and it is a little bit like liking in one respect, because what you are pointing out is a shared identity with your audience or your influence target or whatever your situation is. And it’s a little bit like liking because it’s also something that you might have in common, but it is deeper than that. So if you are of the same tribe, speaking in a sort of metaphorical sense, you will be more persuasive.

28:00 Roger Dooley: And at first, I had a little bit of difficulty sorting out the two, but I think a great example of this is, and there’s actually a lot of psychological literature. Years and years ago, a guy named Henri Tajfel conducted an experiment where he was able to divide a group into two smaller groups, create a totally arbitrary distinction between the two like, “Okay, you folks have a blue sticker on your monitors and you folks have a green sticker on yours,” and in a matter of minutes would have the two groups identifying as being part of their group and the other group as an “out” group, where they would actually be very supportive of their own group and derogatory toward the other group.

28:48 Roger Dooley: Now these were people who all just sort of walked into the room to begin with not knowing each other, or perhaps knowing each other casually. And with a little bit of manipulation, he was able to divide them into two groups. And if you look at the way Apple has marketed its products over the years, it has been all about shared identity, going all the way back to the 1984 commercial, they presented the non-Apple people as this group of faceless drones, gray people listening to this sort of Orwellian guy in a big screen. Then in lemmings, it was even of the sharper distinction, where the other group were lemmings marching over a cliff, where the Apple people, or Mac people, were heroic, human and thought for themselves. And then that carried forward certainly through the years, but they really brought it back strongly when they had the, “I’m a Mac; I’m a PC” commercials, where once again, the in group, the Mac group, were young, cool, hip and the PC group were sort of nerdy, bumbling folks, and they’ve really exploited that shared identity and that’s one reason why Mac users historically have been so fanatical about their products.

30:08 Roger Dooley: And you can’t say something, even an honest criticism, without them jumping all over you and defending the product. So now, unfortunately, perhaps with the proliferation of the iPhone, I think that identity has been diluted a little bit since now, a huge swathe of the population is part of that group, so it’s a little less effective.

30:30 Michael Port: Yeah. And interestingly enough, you don’t see those commercials anymore.

30:34 Roger Dooley: No, no, you don’t. And so, I think that shared identity, if you can find something that you have that is really deeper than liking… My pet ownership thing is a liking thing, but if I were able to identify a common, perhaps an ethnic background, religious background, or even in the case of my IT service providers, I started off by showing them that I was part of that IT service provider tribe, or at least I had been.

31:07 Michael Port: Yeah. That’s so interesting. One of the examples that Robert gave in the beginning of “Pre-suasion” was fascinating to me. He followed around a number of different top-performing sales people and they didn’t know what he did. He went and acted like he was trying to get a job there and he would shadow the more successful folks, because that’s how they train the sales people. And there was one guy who… So one company he went to, they sold fire alarm systems for residential homes, and the guy that was the top performer, he killed everyone. He just was by far, the best in the company and he really, really wanted to shadow him. At first, he’s like, “No, no, no. Nobody comes with me. I do my thing, that’s it.” And he was able, because it was Robert, I imagine, was to persuade him to take him on, and he did something that he had never seen done before.

32:12 Michael Port: When he was sitting with the folks at their house, he would have them take a test. Now the test, he said, “Well, this is a timed test. You need to take it straight through, because we need to see just how much you know about a fire emergency. How to handle it, what to do, because you might be surprised that you don’t know quite as much as you think you do, and this is an important topic.” So as soon as he had them start with that he said, “Oh, my God. I can’t believe it, I left one of my important books in the car. I need to go get it but I do not want to stop the test, because you’ve already started it. We’d have to go back to the beginning and start again, so do you mind if I let myself out and then let myself back in?”

33:00 Michael Port: And of course they say, “No, no, no. That’s perfectly fine.” Well, what Robert identified was that this one technique that this guy was using was the primary reason for the high level of sales he was making because, well, who do you let come in and out of your house without being there? Just let them in and out? People you trust, people that you’re close to, your family members. Well, through that particular technique, he built a certain amount of trust with them. Now, would they leave the house to this fellow for weeks at a time? Probably not. He doesn’t have that level of trust, but there was this implied trust, because they allowed him to go in and out of their house without being checked. I thought that was fascinating.

33:51 Roger Dooley: Yeah. That’s one of his other principles, which is consistency, and basically, we have a tendency to try and behave in a consistent manner. And one of his classic experiments, this goes all the way back to his original “Influence” book, was an experiment they did in a couple of neighborhoods in California, and it went out and asked people if they could put up a safe driving sign in their front yard. And this is gonna be a 3 foot by 6 foot sign and they made some comments about, “We’ll try and minimize damage to your landscape when we install this.” And so, obviously, not an attractive prospect for people and amazingly enough, they got, I think about 20% of the people to agree to do that, which I think would be more like 0% in my neighborhood, but in any case, they managed to get some people to commit to doing it. With another group in a very similar neighborhood, they went around and they asked, “Would you put this little sticker for safe driving in your window?” And it was a very tiny little sticker, and there they got 100% compliance, because who’s gonna argue about that? This little sticker in the window and no big deal.

35:01 Roger Dooley: Then a couple weeks later, they went back to that group that had put the little sticker in their window and presented them with this option of putting this giant sign in their front yard with potential damage to their landscape. And in that case, three-quarters of the people said they would do it. And that seems remarkable to me again, too. It must have been a more accepting time or something, but nevertheless, that illustrates the principle of consistency because having had this little sign promoting safe driving in their window for a couple of weeks, it would be inconsistent for them to reject the larger sign.

35:41 Michael Port: It’s fascinating and it’s the opposite of what we might think when we think of consistency. We might think, “Well, if we want to be influential, we need to be consistent.” But what this is demonstrating is that people will act consistently with you in accordance to the relationship they think they have with you. So if they trust you in one area, that they’re much more likely to trust you in the other area. Am I on the right track here?

36:12 Roger Dooley: Yeah, well, exactly, because they trusted that sales person with this, which is a relatively minor thing, let yourself out, and then let yourself back in. That was fine, so they were more inclined to trust that person then when it came to actually signing the contract.

36:29 Michael Port: As you know, I also have a business called Book Yourself Solid worldwide and for 13 years, the company has been training people on how to develop and grow small businesses. And often people will come in at the beginning and they’ve got a couple different things they’re working on. They wanna serve a couple different markets and offer a couple different solutions as service providers. And we always discourage that, for a number of different reasons. But one of them is that you don’t yet have enough trust to get someone to go from one to the other, because you’ll be a little bit confusing to them. They don’t know, “Well, are you an expert in this? Are you not an expert in this?” That’s unusual, it’s unlikely that somebody would do a number of those different things, and actually be a true expert in each one of those areas.

37:21 Michael Port: But if you have been serving people in one area for a long, long time and you’re really good at it, and they trust you, and then you offer another type of service or product that is seemingly very different than the first one, they are more likely to raise their hand and say, “Yeah, I’ll try that.” Because they will act consistently across those offerings once they have a certain amount of trust with you. But if they don’t know you from Adam, they’re not gonna pick either one, because they don’t yet have trust in your ability to deliver. So, for 13 years, my company delivered services around Book Yourself Solid. And then about four years ago, I moved the business, or I added another business entirely around public speaking. And immediately, the folks from the Book Yourself Solid side came running over to the Heroic Public Speaking side, and I was able to build that so quickly, much more quickly than I would have if I had tried to do both of those things at the same time from the beginning.

38:30 Roger Dooley: Right, well, I think trust is important and clearly, you had built that trust with your first batch of customers, and were more successful in selling the second product to them. I think another way of doing that too would be getting a smaller commitment, and then before asking for a really big commitment that may enable you to build that trust and then get them to commit to a larger order of product or a larger service commitment, or whatever. Although, there’s an interesting variation on that technique, and that is if you ask somebody for big commitment. Say, so you’re selling a product and you really would like them to evaluate the product, take a trial order and see if they like it, like in a B2B situation. Instead of going in and saying, “Okay, we can save you money if you make a six-month commitment. This is all the money we can save you, or whatever,” and hope that they go with that, what you do is you ask for a large commitment, ask for that six-month order, 12-month order, or whatever, knowing that they’re going to say, “No, I don’t think so.” And then, you ask them for the small trial order and having refused you the first time, oddly enough even though you might think that consistency would argue against that, they are more likely to say, “Okay, I will do the small order, the trial order.”

40:00 Michael Port: And anchoring plays a part there too, I imagine.

40:02 Roger Dooley: Yeah, I’m sure it does, but there’s quite a bit of research on that that shows that works, so you ask, you get the no first and then you get the yes. And the experiment there had people who were asked to commit. Subjects were asked to commit to a volunteer program. And one volunteer activity was spending a couple hours one evening tutoring kids, and the other was to show up Saturday mornings for four hours for 10 weeks. So clearly one was a really very big ask, and the other was a rather small ask. And they found that when they simply asked the folks for the two-hour commitment, they got a pretty good number. I figure it was 17% or something said they would do it. When they presented the two options together, it was a little bit higher percentage. So apparently, the contrast between the really big ask and the little ask improved the response a little bit, to I think 25%. But then, they tried the approach I just described which is first, they asked people to do the 10-week four hours a day commitment and 100% said no, of course, ’cause that’s rather unattractive prospect. But then, they asked for the small commitment and a much higher percent, something like 50% said they would do it.

41:23 Michael Port: That’s fascinating. Some of these principles we may have heard of or we may feel, “Oh, intuitively I get that. I should have reciprocity and that’s important, I should flatter people. I wanna create unity, consistency, etcetera.” But what I encourage folks to do is to take all of these principles and look at the presentations you give and see if you are leveraging these principles throughout your speeches. And if you’re not, how can you? How can you find ways to leverage liking, social proof, reciprocity, anchoring, flattery, unity, consistency? And I think that if you read Brainfluence, which is Roger’s book, and of course, you can read either of Robert Cialdini’s books as well, Influence or his new one, Pre-suasion, but Roger’s book is fantastic, absolutely worth every second of the time that you’re gonna take to read it.

42:27 Michael Port: And go find out more at rogerdooley.com, that’s R-O-G-E-R-D-O-O-L-E-Y, rogerdooley.com. And of course on Twitter, @rogerdooley, and anywhere books are sold, you’ll find “Brainfluence”. Thank you so much, Roger. I’m just so happy we finally got you on the podcast. You’re a wonderful, wonderful person, and just always get me thinking, so thank you.

42:53 Roger Dooley: Well, I’m excited to finally make it here too, Michael, and particularly after our unfortunate re… Especially for you, rescheduling the last time, so really appreciate it, glad to be here.

43:02 Michael Port: Fantastic. So guys, keep thinking big about who you are and what you offer the world. I never take this opportunity to be in service of you for granted, it’s a privilege, and an honor, and we’ll talk to you next time. Bye for now.